Armenian Apostolic Church

Some councils which were recognized by the Latin and Byzantine Orthodox Churches as Ecumenical were denied according to the councils of the Armenian Church.

The councils which were not recognized by the Armenian Church as Ecumenical are the following: the Council of Chalcedon (451), the Second Council of Constantinople (553), the Third Council of Constantinople (681) and the Second Council of Nicaea (787).

In 451 the Council of Chalcedon, the Universal Church realized its first divergence because of the dangerous ideas put forward regarding the problem of the human and divine nature of Christ. Some oriental bishops did not accept the conclusions of the Chalcedonic Council and were thus separated from the West. Among the oriental Orthodox Church family are the Armenian Apostolic, Coptic, Ethiopian, Assyrian, and Indian Malabar. In fact, Armenian Church did not participate in the Council of Chalcedon (451), because in 451 Armenia were having one of the important battles of his history, Battle of Vartanats. The Armenian church has been labeled monophysite because they rejected the decisions of this council, which condemned monophysitism.

The Western Church proceeded with its activities cutting off ties with the Oriental Orthodox Churches. But later on different inner divergences took place in the West. In 1054 the church was divided into the Roman Catholic and Byzantine Orthodox Sees after coming to an insoluble disagreement over the theological problem of the origin of the Holy Spirit.

The head of the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church is Jesus Christ. The Supreme Spiritual and Administrative leader of the Armenian Church is His Holiness Karekin II, Supreme Patriarch and Catholicos of All Armenians, who is the worldwide spiritual leader of the Nation, for Armenians both in Armenia and dispersed throughout the world. He is Chief Shepherd and Pontiff to 9,000,000 Armenian faithful, he is the Pope for Armenians. The spiritual and administrative headquarters of the Armenian Church, the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, located in the city of Vagharshapat, Republic of Armenia, was established in 301 AD and seventeen centuries later continues to guide the devoted nation and people on the luminous paths of fulfilling the primary mission of the Church - leading people to God. “Catholicos” is derived from the Greek word Katholikos, which means Universal. When the structure of the Armenian Church was created, the title was originally used to indicate the highest leader of the church. St. Gregory the Illuminator, the first Catholicos of All Armenians, was still subordinate to the See of Caesarea in Cappadocia and the chief bishops of Georgia and Albania, although dependent on the Catholicos of Armenia. Under King Pap and the Catholicos Hooszik I, Armenia asserted its independence of Caesarea.

On the other hand the Armenian Catholic Church, which is an Eastern Rite church under the authority of the Pope in Rome.

St. Gregory the Illuminator is the Patron Saint of the Armenian Church. He is referred to as "St. Gregory the Illuminator," or "Soorp Krikor Lousavorich" because he spread the light of Christ and converted the Armenian people to Christianity.

While Christianity was practiced in secret by a growing number of people in Armenia during the first and second centuries, it was St. Gregory (302-325) and King Trdat III (287-330) who in 301 A.D. officially proclaimed Christianity as the official religion of Armenia and thus made Armenia the first nation in world history to adopt Christianity as the state religion

The story according to the Holy Tradition is as follows: As part of a planned plot, the Persian King Ardashir I, sent a trusted friend, Anak, to Armenia, to kill King Khosrov. During a hunting trip, Anak killed the King and ran away. The loyal men of the King pursued Anak, who was subsequently killed. The dying King gave orders to exterminate Anak's family. Only one infant escaped this slaughter, and was rushed by his nurse to the city of Caesarea. This nurse happened to be a converted Christian. She brought up her charge in the Christian faith and gave him a Greek name, Gregory. St. Gregory became a devout Christian; married a Christian lady named Mariam, and had two children, Verthanes and Arsitakes.

When the Persian King heard that the King of Armenia was killed, he overran the country and established Persian rule in Armenia. Two of the children of King Khosrov were saved. The Princess Khosrovidought was taken to one of the inaccessible castles of the country, while Prince Trdat was taken to Rome. Trdat received a thorough Roman training. When he became a mature young man, able to rule a kingdom, he was sent by Rome to occupy Armenia, recover the throne of his father, and become a Roman ally.

As Trdat was returning to Armenia, most of the loyal Armenian feudal lords, who were in hiding, accompanied Trdat. St. Gregory also decided to go along with him. Nobody had any knowledge of his background or of his religious convictions. Trdat found out that St. Gregory was a well-educated, dependable and conscientious young man. He appointed him as his secretary.

After winning back Armenia, Trdat gave orders for a great and solemn celebration. During the festival, St. Gregory was ordered to lay wreaths before the statue of the goddess Mother Anahit, who was the most popular deity of the country. St. Gregory refused and confessed that he was a Christian. One of the king's ministers decided to reveal St. Gregory's secret. He told the King that St. Gregory was the son of Anak, the killer of his father King Khosrov. Trdat gave orders to torture St. Gregory. When St. Gregory stood fast, the King ordered him to be put to death by throwing him into a prison-pit (Khor Virab) in the town of Artashat to be starved to slow death.

Through divine intervention and with the assistance of someone in the Court, St. Gregory survived this terrible ordeal for thirteen years. It is thought the Princess Khosrovidought, the King's sister, had found a way to feed St. Gregory in the dungeon.

During that very year the king issued two edicts: the first ordered to arrest all the Christians in Armenia confiscating their property, the second ordered to put to death those who hid Christians. These edicts show how dangerous was Christianity for the State and for heathen religion in the country.

This undertaking of persecution revealed the presence of a group of women, who were peacefully and secretly living in the capital city of Vagharshapat. The Holy Tradition claims that a group of Roman Christian virgins ran away to the East in order to escape the persecutions of the Emperor Diocletianus. After visiting Jerusalem and paying tribute to the holy places, the virgins came to Edessa, then crossed the frontiers of Armenia and settled down in vineyards not far from Vagharshapat. The leader of these pious women was Gayané. There was also among them a beautiful maiden called Hripsimé, who King Trdat wanted to have as his concubine. Hripsimé refused and resisted the King's advances and finally fled from the Palace. This was too much for King Trdat and he mercilessly ordered to have all the women killed. They were 32 in number. Gayane¢, the mentor of the virgins and two others living in the southern part of the town and a sick virgin were tormented in the vineyards. The execution of the Hripsimian virgins took place in 300/301. This slaughter of innocent women and his frustration at being rejected threw the King into melancholy and finally made him insane. He could not attend the affairs of the state. In the 5th century people called this "pig’s illness", which is why sculptors portray the king with a pig’s head.

His sister, Khosrovidukht, did everything to bring her brother back to his senses. Then one day in a dream, she saw St. Gregory coming out of the dungeon and healing her brother. She told the people at the Court of her dream, and revealed that he was alive. They sent men to the dungeon to bring him out. As he emerged, out came a man with a long beard, dirty clothes and darkened face. But his face was shining with a strange and strong light. He immediately gathered and buried the remains of the virgin-martyrs and thereafter preached the Gospel for a period of time and healed the King. Trdat III proclaimed Christianity as the state religion of Armenia after which the entire royal court was baptized. King Trdat was cured and became a new man. He said to St. Gregory: "Your God is my God, your religion is my religion." From that moment until their death they remained faithful friends and worked together, each in his own way, for the establishment of the Kingdom of God in Armenia.

Today there are large Armenian Orthodox congregations in many middle-eastern countries outside Armenia. Of particular importance is the Armenian Apostolic Church of Iran (see also Christians in Iran) where Armenians are the largest Christian ethnic minority.

Other large Armenian Orthodox congregations are in the USA and in many Western European countries.

Article based on Wikipedia article.

Ejmiatsin Town

|

The Town of Ejmiatsin, now officially known as Vagharshapat is primarily known as the site of the Ejmiatsin Cathedral Compound, which is the headquarter of the Armenian Church. In addition to the compound, there are the churches of Hripsime, Gayane and Shoghakat. The town is also known for it's kyufta, a traditional Eastern Armenian dish, and even has a "Kyufta Street", with a number of kyufta specialists.

|

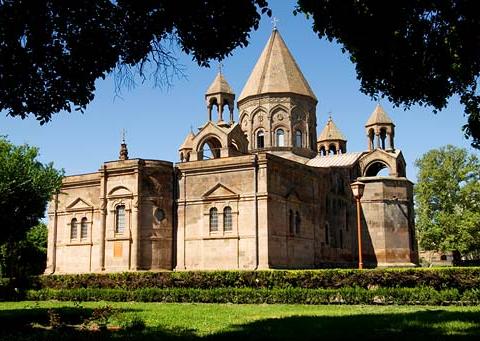

Ejmiatsin or (Etchmiadzin) Cathedral

Ejmiatsin Cathedral Compound

4th-19th Centuries - Ejmiatsin Town, Armavir Marz

The cathedral, built in 480, is located in a walled compound with gardens and various structures.

The word "Ejmiatsin" means The coming of the only-begotten, and the cathedral was built on the very spot Grigor Luysavorich (St. Gregory the Illuminator) dreamt Jesus Himself descended to from heaven to show him where He wanted the church to be built.

It is a scenic place to visit. The main church structure is pretty large, however the majority of the interior is dedicated to uses other than worship and the area you enter is much smaller than the size of the entire complex. It is a traditional Armenian design with a belfry and a number of rotundas. Most of the exterior is plain until you make it around to the entrance which is intricately carved and very beautiful. You must not leave until you get into the Manoogian Museum. (Entrance through the large arch across from the cathedral entrance) This structure contains numerous cool paintings, souvenirs, religious artifacts, and illuminated manuscripts so insist on seeing it. Another secret is a fire pit beneath the altar. This is where pagans worshipped fire before Christianity. It is in the small museum in the main cathedral, with the entrance to the right of the altar. There are some religious artifacts in display cases, but you usually need to ask to be shown the fire worshipping pit, at which time a small donation is hinted at. Above the door which descends into the fire pit area is the lance ("Geghard") which is said to have pierced Christ's side. The original structure was added to so much over the years that not much remains now. There was an even earlier church on the same site which was supposed to have been built when Armenia was converted to Christianity. However, Ejmiatsin was yet the oldest church in the USSR.

Make sure to wander around the gardens to get a look at the carvings and khatchkars.

The traffic square adjacent to the compound is ringed with very nice models of some Armenian churches throughout the country.

Echmiadzin is the center of the Armenian Church. It is where the Catholicos Of All Armenians lives, and the location of the Ejmiatsin Cathedral.

Ejmiatsin (known as Vagarshapat before 1945) was founded by King Vagarshak (117-140) in the place of Vardkesavan, an ancient settlement of the third-second centuries B.C. In view of the might of the town's fortifications — fortress walls, ramparts and moats — the Romans, upon the second destruction of Artashat in 163, transferred the capital of Armenia to Vagarshapat which, after Christianity was proclaimed the state religion in 301, became the country’s religious centre as well.

Vagarshapat was repeatedly destroyed by enemies. In particular. it was left in ruins by Persian troops in 364-369. However, the improvement of economic welfare in the long periods between wars made it possible to do extensive construction work and to erect in the town large structures which played an extraordinary role in the development of national architecture.

On the territory of Vagarshapat there have survived monuments of various periods of Armenia's history. Urartu arrows have been found in the temples of Zvartnots Cathedral and Ejmiatsin, and remnants of an ancient hearth of a heathen tabernacle — in the altar part of the latter. Greek and Latin epigraphic inscriptions, cut on tombstones, date back to the epoch of the Armenian Hellenistic culture. Architectural fragments, found by chance, such as an ornamented cornice in the masonry of the foundation of Hripsime church, are evidence of a high artistic standard of the structures of that time.

|

Ejmiatsin cathedral was the main Christian temple of Vagarshapat. Gayane, Hripsimeh, Shoghakat and other churches, built at various times in place of small and not too expressive fourth-century chapels, complement it from the point of view of architecture and layout. Situated relatively close to Ejmiatsin cathedral, they are perceived as important components of a single architectural ensemble which changed after each new temple was built. The low residential structures all around set off to the best advantage the grandeur of these edifices and their domination in various parts of the city.

Ejmiatsin cathedral ("the place where the homogeneous come together") is the most ancient Christian temple of Armenia. It was built in 301-303 by Grigor Luysavorich (St. Gregory the Illuminator), the founder of the Armenian Gregorian church, next to the king's palace, in place of a destroyed heathen basilica. The monastery which took shape around the cathedral is the residence of Catholicos. the head of the Armenian clergy. Scientists' opinions as to the original appearance of Ejmiatsin cathedral vary. According to T. Toramanian's hypothesis, the cathedral had the shape of a basilica at the beginning of the fourth century and, after reconstruction at the end of the fifth century, its plan became rectangular, with a four-apse cross and rectangular corner annexes fitted into it. The building had five domes. In the seventh century the apses were moved outside the limits of the rectangle, which gave the building the cross-cupola outside shape. |

Proceeding from the material of excavations, however, A. Sainyan established that the basilical composition of the original temple was changed to a cross-shaped one with the central dome in 483. What remained of the basilica were only small vari-coloured cubes in the altar apse (remnants of the stone and small mosaics, often gilded, which decorated it) and the bases of four pylons which were used as the inner abutments of the central-dome building. That was one of the most ancient Christian temples of that type, which played a tremendous role in shaping the concentric buildings of the early Christian period in Armenia and which makes it possible to ascertain the origin and classification of types.

At the beginning of the seventh century the building's wooden dome, probably octohedral and shaped like the roof of the Armenian peasant home (as the domes of Khaikavanke and Horashene churches in Van) was replaced by a stone one. This composition of the cathedral has come down to our day almost unchanged.

The cupola's abutments, cross-shaped in plan, are connected with each other and with the walls by arches underlying the vaults — cross-shaped in the coiner sections and semi-circular in the middle sections; the apses arc crowned with conchs. The arrangement of the ceilings at various levels causes the interior to taper off to the central dome. Harmonious proportions and sharpness of individual elements impart great artistic expressiveness to the interior whose shapes are simple and clear-cut. The building’s outward appearance. which underwent certain changes in the 17th and subsequent centuries, was no less clear-cut.

In the 17th century (1653-1658), for instance, a new cupola and a three-tier belfry were built, the latter in front of the western entrance to the cathedral. The decoration of the cupola and, especially, of the belfry is in sharp contrast with the ascetic shapes of the ancient parts of the cathedral. In accordance with the artistic tasks of that epoch, they were decorated with abundant decorative carvings. The ornaments are not only geometrical, but floral as well, the latter taking up large spaces. The columns of the arcature of the cupola drum and of the lower tiers of the belfry are twisted. The representations of ox and snake heads are of symbolic significance. In the corners of the gables of the belfry's facades there are busts of clergymen; on the vaulted ceilings — six-winged seraphs; and on the medallions of the tympans of the dome’s arcature — saints.

The six-column rotundas on four-pillar bases, built at the beginning of the 18th century over the northern, eastern and southern apses, have given the cathedral a five-dome crowning. The interior murals, created by the Armenian painter Nagash Ovnatan in 1720, was restored and elaborated upon by his grandson, Ovnatan Ovnatanian, in 1782-1786. In 1955-1956, the interior murals of the cathedral and of the belfry were renewed by a group of Soviet artists under the leadership of L. Durnovo. This rich and variegated floral ornament — orange-red on the altar wall and lilac-blue in other places — is an outstanding work of 18th-century Armenian art. Ovnatan Ovnatanian also painted oil canvas pictures on religious themes for Ejmiatsin cathedral (some of them are on display in Yerevan picture gallery). These early works of Armenian painting already show features of realism.

Rich gifts of church-plate and valuable works of applied art kept pouring into Ejmiatsin as the residence of the Catholicos. Three premises, now housing the monastery’s museum, were annexed to the eastern side of the cathedral in 1869 to keep these gifts in. The architectural elements of the annex — twin windows with transom bars, protruding lock plates and frontons show the influence of Russian architecture of the second half of the 19th century.

|

Meriting special attention among the museum exhibits are gorgeous church attires embroidered with gold and pearls, printed curtains, embroidered coverlets, crosses, croziers, all kinds of ritual vessels of silver gold, ivory, adorned with filigree work and jewels. Most of these articles date back to the 17th-19th centuries. There are older works of art, too. A tenth-century crucifix of Avutstar monastery is one of the oldest wooden bas-reliefs in Armenia to have come down to this day. The plasticity of the naked body, the expressiveness of the faces and the tension of poses are conveyed most convincingly. In G. Ovsepian's opinion, the presence of heads in the ornament implies that there existed in Armenia metal crucifixes which have not survived. Of interest are the chairs of the 17th century Catholicoses decorated, besides mother-of-pearl and ivory incrustation, with a complicated geometrical and floral carving and wrought iron heads and paws of lions. There are also rare ancient coins, various relics and ancient manuscripts with headpieces and miniatures.

The most valuable of Ejmiatsin's manuscripts is the world famous "Ejmiatsin Gospel" of 989, now in Matenadaran (Ancient Manuscript Research Institute of the Armenian Academy of Sciences, No. 2374), a copy of the ancient original made by scribe Ovanes in Bkheno-Noravank monastery, the summer residence of Syunik bishops. This is a monument of three stylistically different epochs. The end miniatures of the 6th-7th centuries, reflecting the influence of Hellenism. are close in their colour scheme and pastel technique to the encaustic icons of the 5th-6th centuries and, in the expressiveness of the typically Armenian faces, to the interior murals of Stepanos church in Lmbat (the early 7th century). In the "Adoration of the Magi" gold, in combination with dense and vibrant tones, makes for utter expressiveness. The national types of faces, with large features and intense look in their eyes, are also most expressive. |

The opening miniatures of the late 10th century stand out for vivid colour, gracefulness and smoothness of ornament and realistic representation of birds and plants. In the galleries there are marble columns with magnificent capitals. The representation of Christ as a young man and the Apostles is quite unusual. They are shown in light-toned dresses. The monumentality and laconicisrn of style make these miniatures akin to the murals and bas-reliefs of the Church of the Cross (915-921) on Haghtamar Island.

The ivory binding is a superb work of art by Byzantine carvers of the 6th-7th centuries, It is composed of relief plates showing scenes from the Gospel. At the top there are flying angels carrying a cross enframed in a wreath — a theme well known from Byzantine works of Constantinople, Ravenne and Alexandria and from earlier stone reliefs of Armenia such as those of Ptgni temp]e of the 6th century and from later khachkars, such as Amenaprkich in Haghpat (1273). The centre of the front part is taken up by a representation of the Holy Virgin with the infant; all around it there are various scenes from the Gospel.

Some of the exhibits of Ejmiatsin monastery are put on display on the territory of the monastery’s yard. Meriting attention are the khachkars — one of the Amenaprkich type of 1279, and the other from the old Dzhuga cemetery (17th century) covered with intricate floral and geometrical ornaments, pictures of birds and animals and various scenes featuring figures of men and saints.

On the monastery yard there are the buildings of the Catholicosat, a school, a winter and summer refectories, a hostel, Trdat’s gate and other structures. They were built in the 17th-19th centuries in place of earlier buildings.

The 19th century dwelling houses of Ejmiatsin are of artistic value. They are distinguished by unusual layout and appearance. The open-work carving of wooden street balconies and yard galleries is a superb piece of folk craftsmanship. The carving motifs are stylistically connected with the ornamentation of the religious buildings of Echmiadzin of the 17th-18th centuries.

(aka Etchmiadzin, Etchmiadtsin, Echmiatsin, Echmiadzin)

Armenian Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia

Seat of the Catholicos is in Antelias, Lebanon. It was located in Sis, Cilicia prior to that in the Ottoman Empire, but forced to relocate due to the Armenian Genocide.

Current Catholicos is His Holiness Aram I

Catholicos Aram I

Photo by Arsineh Khachikian

Photo by Arsineh Khachikian

His Holiness Aram I was born in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1947. He studied at the Armenian Theological Seminary in Antelias, the Near East School of Theology (Lebanon), the American University of Beirut, the Ecumenical Institute of Bossey (Switzerland) and the Fordham University (New York, USA). His major areas of specialization are philosophy, systematic theology and Near Eastern Church history. He holds an M. Div., an S.T.M., a Ph.D. and several honorary degrees.

Catholicos Aram I was ordained as a celibate priest in 1968. Two years later he obtained the title of Vartabed, or Doctor of the Armenian Church. Late in 1978, while studying at the Fordham University, he was elected Locum Tenens for the Diocese of Lebanon, and a year later the Primate of Lebanon. In 1980, he received episcopal ordination.

Called to serve as Primate of the Armenian Diocese of Lebanon at the most critical period of Lebanese history, His Holiness has made the following priorities the basic objectives of his pastoral work: reorganizing parishes and schools, reactivating social and church organizations, renewing community leadership and strengthening relationships between the Christian and Moslem communities.

On 28 June 1995, he was elected Catholicos by the Electoral Assembly of the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia. He was consecrated on l July 1995.

During his many years of service, His Holiness displayed a wide range of interests and assumed important responsibilities in the Armenian Catholicosate of Cilicia, as well as in the world-wide ecumenical movement.

For many years he lectured on Armenological and theological subjects at the Armenian Seminary and at the Haigazian University (Lebanon). In addition to his numerous articles in Armenian, English and French (some of which have been translated into Arabic, German, Spanish and Swedish) which have appeared in local and international periodicals

Saint Gregory the Illuminator

St. Gregory statue at the Vatican

|

Saint Gregory the Illuminator or Saint Gregory the Enlightener (Armenian: Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ translit. Grigor Lusavorich, the founder and patron saint of the Armenian Apostolic Church, was born about.

He belonged to the royal race of the Arsacides, being the son of a certian Prince Anak, who assassinated Chosrovs of Armenia, and thus brought ruin on himself and his family. His mother's name was Okohe, and the Armenian biographers tell how the first Christian influence he recived was at the time of his conception, which took palce near the monument raised to the memory of the holy apostle Thaddeus. Educated by a christian nobleman, Euthalius, in Caesarea in Cappadocia, Gregory sought, when he came to amn's estate, to introduce the Christan doctrine into his native land. At that time Tiridates I, a son of Chosroes, sat on the throne and, influenced partly it may be by the fact that Gregory was the don of his father's enemy, he subjected him to much cruel usage, and imprisoned him for fourteen years. It would be useless to recount the various forms of torture which the orthodox accounts represent the saint to have endured without permanent hurt; almost any one of hi twelve trials would ghave been certain death to an ordinary mortal. But vengeance and madness fell upon the king, and at length Gregory was called forth from his pit to restore his royal persecutor to reason by virtue of his saintly intercession. |

A number of Homilies, possibly spurious, several prayers, and about thirty of the canons of the Armenian Church are ascribed to Gregory. The homilies appeared for the first time in a work called Haschacnapadum at Constantinople in 1737; a century afterwards a Greek translation was published at Venice by th Mekhiterists; and they have since been edited in German by J.M. Schmid (ratisbon, 1872). The original authorities for Gregory's life are Agathangelos, whose History of Tiridates was published by the Mekhitarists in 1835; Moses of Chorene, Historiae Armenicae; and Simeon Metaphrastes. A Life of Gregory by the vartabed Matthew, published in Armenian at Venice in 1749, was translated into English by Rev. S.C. Malan, 1868.

from the 9th edition (1880) of an unnnamed encyclopedia

Armenian Christmas

Why Do Armenians Celebrate Christmas on January 6th?

by Hratch Tchilingirian

"Armenian Christmas," as it is popularly called, is a culmination of celebrations of events related to Christ's Incarnation. Theophany or Epiphany (or Astvadz-a-haytnootyoon in Armenian) means "revelation of God," which is the central theme of the Christmas Season in the Armenian Church. During the "Armenian Christmas" season, the major events that are celebrated are the Nativity of Christ in Bethlehem and His Baptism in the River Jordan. The day of this major feast in the Armenian Church is January 6th. A ceremony called “Blessing of Water” is conducted in the Armenian Church to commemorate Christ’s Baptism.

It is frequently asked as to why Armenians do not celebrate Christmas on December 25th with the rest of the world. Obviously, the exact date of Christ's birth has not been historically established—it is neither recorded in the Gospels. However, historically, all Christian churches celebrated Christ's birth on January 6th until the fourth century.

According to Roman Catholic sources, the date was changed from January 6th to December 25th in order to override a pagan feast dedicated to the birth of the Sun which was celebrated on December 25th. At the time Christians used to continue their observance of these pagan festivities. In order to undermine and subdue this pagan practice, the church hierarchy designated December 25th as the official date of Christmas and January 6th as the feast of Epiphany. However, Armenia was not effected by this change for the simple fact that there were no such pagan practices in Armenia, on that date, and the fact that the Armenian Church was not a satellite of the Roman Church. Thus, remaining faithful to the traditions of their forefathers, Armenians have continued to celebrate Christmas on January 6th until today.

In the Holy Land: January 18th

In the Holy Land, the Orthodox churches use the old calendar (which has a difference of twelve days) to determine the date of the religious feasts. Accordingly, the Armenians celebrate Christmas on January 18th and the Greek Orthodox celebrate on January 6th. On the day before Armenian Christmas, January 17th, the Armenian Patriarch together with the clergy and the faithful, travels from Jerusalem to the city of Bethlehem, to the Church of Nativity of Christ, where elaborate and colorful ceremonies take place. Outside, in the large square of the Church of Nativity, the Patriarch and his entourage are greeted by the Mayor of Bethlehem and City officials. A procession led by Armenian scouts and their band, advance the Patriarch into the Church of Nativity, while priests, seminarians and the faithful join in the sing of Armenian hymns. Afterwards, church services and ceremonies are conducted in the Cathedral of Nativity all night long and until the next day, January 18th.

Source: St. Andrew Information Network Top