|

Armenian

Language

Armenian

is an

Indo-European language spoken in the

Caucasus

mountains and also used by the

Armenian Diaspora.

It is its own independent branch of the

family of the Indo-European languages.

From the modern languages Greek seems to

be the most closely related to

Armenian.

The

Armenian language dates to the early

period of Indo-European differentiation

and dispersion some 5000 years ago, or

perhaps as early as 7,800 years ago

according to some recent research.

Graeco-Armenian hypothesis

Armenian is

regarded by some linguists as a close

relative of

Phrygian.

Many scholars such as Clackson (1994)

hold that

Greek is

the most closely related surviving

language to Armenian. The

characteristically Greek representation

of word-initial

laryngeals

by prothetic vowels is shared by

Armenian, which also shares other

phonological and morphological

peculiarities of Greek. The close

relatedness of Armenian and Greek sheds

light on the

paraphyletic

nature of the

Centum-Satem

isogloss. Armenian also shares major

isoglosses

with Greek; some linguists propose that

the linguistic ancestors of the

Armenians and Greeks were either

identical or in a close contact

relation. However other linguists

including Fortson (2004) comment "by the

time we reach our earliest Armenian

records in the 5th century A.D., the

evidence of any such early kinship has

been reduced to a few tantalizing

pieces."

Iranian

influence

The

Classical Armenian language (often

referred to as

Grabar, literally

"written (language)") imported numerous

words from Middle Iranian languages,

primarily Parthian, and contains smaller

inventories of borrowings from Greek,

Syriac, Latin, and autochthonous

languages such as

Urartian. Middle

Armenian (11th–15th centuries AD)

incorporated further loans from Arabic,

Turkish, Persian, and Latin, and the

modern dialects took in hundreds of

additional words from Modern Turkish and

Persian. Therefore, determining the

historical evolution of Armenian is

particularly difficult because Armenian

borrowed many words from Parthian and

Persian (both Iranian languages) as well

as from Greek.

The large

percentage of loans from Iranian

languages initially led linguists to

classify Armenian as an Iranian

language. The distinctness of Armenian

was only recognized when Hübschmann

(1875) used the comparative method to

distinguish two layers of Iranian loans

from the true Armenian vocabulary. The

two modern literary dialects, Western

(originally associated with writers in

the Ottoman Empire) and Eastern

(originally associated with writers in

the Russian Empire), removed almost all

of their Turkish lexical influences in

the 20th century, primarily following

the Armenian Genocide.

While it contains

many Indo-European roots, its phonology

has been influenced by neighboring

Caucasian languages, so that it shares a

three-way distinction between voiceless,

voiced, and ejective stops and

fricatives.

Armenian was

historically split in to two

vaguely-defined primary dialects:

Eastern Armenian, the form spoken in

modern-day Armenia, and Western

Armenian, the form spoken by Armenians

in Anatolia. After the

Armenian Genocide,

the western form was primarily spoken

only by those belonging to the

diaspora.

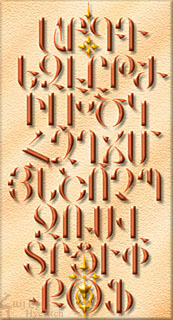

Armenian is

written in the

Armenian Alphabet, created by

Saint

Mesrop Mashtots

in 406 AD.

The Armenians are

a predominantly Christian ethnic group,

primarily of the

Armenian Church.

Whether Armenians are Europeans or not

is a bone of contention, as the people

of

Caucasia

have become increasingly disregarded as

being Europeans over the past couple of

centuries. This process was arguably

accelerating as the term "European"

increasingly is being used to refer to

citizens of the

European Union

rather than peoples of ethnic European

origins, but the recent (2004) inclusion

of Armenia in the EU "New Neighborhood",

which is expected to lead to membership

in the long term will once again swing

the pendulum in the direction of Europe.

Eastern Armenian

Eastern Armenian people,

and the dialect are

basically those

Armenians and the

dialects they speak

which originated in the

Russian and Persian

Empires (basically, the

the former USSR and

Iran). Eastern Armenian

is still written in the

original spelling system

invented by Mesrop

Mashtots

by Iranian Armenians,

but in the former USSR a

new, simplified spelling

system is used.

Western Armenian

Western

Armenian

people,

and the

language,

are

basically

those

Armenians

and the

dialects

they

speak

which

originated

in the

Ottoman

Empire

(basically,

anywhere

outside

of the

former

USSR and

Iran).

Western

Armenian

is still

written

in the

original

spelling

system

invented

by

Mesrop

Mashtots.

One

thing

the

Western

Armenian

language

has

which

Eastern

Armenian

does

not, is

a

special

way to

say "very",

depending

on the

word in

question.

For

example,

instead

of using

shad

which is

the

standard

word for

"very"

in

describing

something

that is

very

black,

the word

sep

can be

used. It

has no

meaning

on its

own, but

in

conjunction

with the

word

black,

sep

sev

comes to

mean

very

black.

Here is

a list

of known

examples.

-

sep

sev,

jep

jermag,

gas

garmir,

gas

gabid,

tep

teghin,

gas

gananch,

lep

letsun,

bas

barab,

mis

minag,

ship

shidag,

dzups

dzur,

chop

chor,

tap

tats,

pas

parag,

nip

nihar

etc...

Armenian

Alphabet

| |

Upper

Case |

Lower

Case |

Eastern

Translit. |

Western

Translit. |

Letter

Name

|

Number

Value

|

|

Ա |

ա

|

a |

a |

այբ

|

1 |

|

Բ |

բ

|

b |

p |

բեն |

2

|

|

Գ |

գ

|

g

|

k |

գիմ

|

3 |

|

Դ

|

դ

|

d |

t |

դա

|

4 |

|

Ե |

ե |

e,ye |

e,ye |

եչ |

5 |

|

Զ |

զ

|

z |

z |

զա |

6 |

|

Է

|

է

|

e |

e |

է

|

7 |

|

Ը

|

ը |

ə |

ə |

ըթ |

8 |

|

Թ |

թ |

t'

|

t' |

թո |

9 |

|

Ժ

|

ժ

|

jh |

jh |

ժե |

10 |

|

Ի |

ի |

i |

i |

ինի

|

20 |

|

Լ

|

լ

|

l

|

l

|

լյուն |

30 |

|

Խ |

խ |

kh |

kh |

խե |

40 |

|

Ծ |

ծ |

ts |

dz |

ծա |

50 |

|

Կ |

կ |

k |

g |

կեն |

60

|

|

Հ |

հ |

h |

h

|

հո |

70 |

|

Ձ

|

ձ |

dz |

ts |

ձա |

80

|

|

Ղ

|

ղ |

gh |

gh |

ղատ |

90 |

|

Ճ |

ճ |

ch |

j |

ճե |

100 |

|

Մ |

մ |

m |

m |

մեն |

200 |

|

Յ |

յ |

y |

h |

հի |

300 |

|

Ն |

ն |

n |

n |

նու |

400 |

|

Շ |

շ |

sh |

sh |

շա |

500 |

|

Ո |

ո |

o,vo |

o,vo |

վո |

600 |

|

Չ |

չ |

ch' |

ch' |

չա |

700 |

|

Պ |

պ |

p |

b |

պե |

800 |

|

Ջ |

ջ |

j |

ch |

ջե |

900 |

|

Ռ |

ռ |

rr |

rr |

ռա |

1000 |

|

Ս |

ս |

s |

s |

սե |

2000 |

|

Վ |

վ |

v |

v |

վեվ |

3000 |

|

Տ |

տ |

t |

d |

տյուն |

4000 |

|

Ր |

ր |

r |

r |

րե |

5000 |

|

Ց |

ց |

ts' |

ts' |

ցո |

6000 |

|

Ւ |

ւ |

u |

v |

ու |

7000 |

|

Փ |

փ |

p' |

p' |

փյուր |

8000 |

|

Ք |

ք |

k' |

k' |

քե |

9000 |

|

և |

ևվ |

yev,ev |

yev,ev |

և |

|

|

Օ |

օ |

o |

o |

օ |

|

|

Ֆ |

ֆ |

f |

f |

ֆե |

|

Upper

Case |

Lower

Case |

Eastern

Translit. |

Western

Translit. |

Letter

Name |

Number

Value |

|

|

TOP

History

Invented in 405 by

Mesrop Mashtots

with the

assistance of Sahak Partev in order to

translate the Bible into Armenian.

First

printed documents appeared in Armenia in

early 16th century. A century later, in

1662, an Armenian cleric, Father

Voskan was sent to Amsterdam by

Catholicos Hakop, to prepare

printing of the Bible in Armenian. Four

years later, the job, which consisted of

casting Armenian letter types, producing

wooden carvings for the illustrations,

etc. was completed, and the first Bible

in the Armenian language was printed in

Amsterdam in 1666.

It is said that

some letters of the Armenian alphabet

were based on the Greek ones. However,

more than a visual similarity, the

Armenian and Greek alphabets are rather

very close in the letter/sound order.

Actually a Greek colleague allegedly

helped Mashtots with creating the

Armenian alphabet.

Furthermore,

the alphabet is composed as a prayer,

beginning with

A

as Astvats (=God) and ending with

K'

as K'ristos (=Christ). The original

alphabet had only 36 letters. Later,

three more characters were added:

-

և

(yev) : actually a conjunction

meaning "and". It is used only in

minuscule. Therefore when using

capitals, it must be written like two

letters-

ԵՎ. On the

beginning pronounced “yev”, in the

middle of the word “ev”.

-

Օ : it is

being used in the eastern Armenian on

the beginning of the words when it is

needed to be pronounced as

“o”,

instead of

“Ո”, which is

pronounced

“vo”

on the beginning of the

words. In western Armenian, it is

commonly used in the middle of the

words.

-

ֆ

(F)

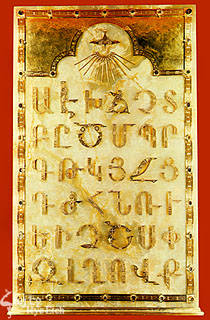

Armenian Alphabet Monument at outskirts

of

Oshakan Village.

Transliteration

The

transliteration system I use is very

simple, based on the Latin character

equivalents assigned to each letter in

the alphabet above. Each letter has an

English equivalent letter, or

combination of letters.

For example, the Armenian

word for

Jacob,

"Հակոբ"

would be pronounced

"Hakob"

in Eastern Armenian, or

"Hagop"

in Western Armenian.

Kalousdian

in Eastern Armenian

Kaloustian

in Western Armenian.

It is important

to remember that the eastern and western

dialects differ in transliteration,

because some Armenian characters are

pronounced differently.

For example, in

Armenian, the equivalent of the English

name

Peter,

is

Petros

in Eastern Armenian, and

Bedros

in Western. As you can see the

P

and the

T

are pronounced

differently in Western Armenian. This

name would be Pedro in Spanish, where

only the letter

T

has changed. This is because the

Armenian alphabet contains a few "middle

sounds" which English has for the most

part lost.

For example, the

P

and

B

sounds have a sound somewhere in between

those two sounds that English speakers

(and often Western Armenians) will have

a very difficult time perceiving. If you

say the English word "sports", you may

notice that you are actually pronouncing

this middle sound without even noticing

it. Most people are not pronouncing a

clean

P,

but something that sounds more like a

B,

but not quite... this is the sound that

Eastern Armenian uses for the second

letter of the Armenian alphabet. Western

Armenians do not use this difference as

much, pronouncing more of a clean

B.

Western Armenian also differs in

vocabulary and conjugation from Eastern

Armenian, which is used in the Republic

of Armenia today.

Dating

Armenian Monuments

Knowledge of the Armenian alphabet is

useful but not essential for

appreciation of Armenia's cultural

patrimony. However, one sure way to

impress on-lookers, including local

worthies, is by deciphering the date on

medieval inscriptions.

Dates are generally marked by the

letters

ԹՎ

or the like, often with a line over,

indicating

"t'vin"

("in the year") followed by one to four

letters, each of which stands for a

number based on its order in the

alphabet. In the Middle Ages, Armenians

used a calendar that started in AD 552

as the beginning of the Armenian era.

To translate into standard years, simply

add 551 to the number. Thus, should you

see an inscription reading

ԹՎ ՈՀԳ,

simply check the alphabet table up and

see that this equals 600+70+3+551= the

year of Our Lord 1224.

TOP

Armenia's

remarkable alphabet

By Ken Gewertz

Harvard University Gazette, MA Nov 3

2005

Saint's sturdy Armenian alphabet focus

of meetings Harvard News Office

In Yerevan,

capital of Armenia, the manuscript

library known as the Matenadaran

possesses an almost sacred status.

Situated on a hill, it is approached by

a long cascade of white marble steps

flanked by statues of the great figures

of Armenian literature. Chief among

these is St. Mesrops Mashtots, who gave

Armenia its alphabet.

According to

James Russell, the Mashtots Professor of

Armenian Studies at Harvard, the

fifth-century saint gave Armenia much

more than an efficient system for

rendering its language into written

form. By means of his invention,

Mashtots gave Armenians a cultural and

religious identity as well as the means

to survive as a people despite the

efforts of larger and more powerful

neighbors to subsume or destroy them.

Armenians pride

themselves on being the first nation to

adopt Christianity, an event that is

supposed to have occurred in the early

fourth century when St. Gregory the

Illuminator succeeded in converting

Trdat, the king of Armenia. But

according to Russell, there is much

evidence that after Trdat's death, the

country was in the process of reverting

to paganism.

"Mashtots'

principal purpose in inventing the

alphabet was to change Armenia's

cultural orientation from the Iranian

East to the Mediterranean West," Russell

said. "He gave Armenia the means and the

incentive to remain Christian."

Having an

alphabet allowed Armenians not only to

translate the Bible into their own

language but works of Christian

theology, saints' lives, history, and

works of classical literature as well.

It also allowed them to develop

scholarly institutions and a literature

of their own.

"Within a

century, Armenians had a library of

classical and Christian learning and

were able to build their own literary

tradition. As a result, they became

independent and almost self-sufficient,

and they became impervious to attempts

by Rome to Hellenize them or attempts by

the Sassanian empire to re-impose

Persian culture on them."

On Oct. 28 and

29,2005, Harvard hosted an international

conference to consider the achievement

of Mashtots, its historical background,

and its wider influence. Organized by

Russell, the conference was sponsored by

the Armenian Prelacy of New York, the

Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian

Studies, and the Department of Near

Eastern Languages and Civilizations at

Harvard. It was held under the patronage

of His Holiness Aram I, Catholicos of

the Great House of Cilicia.

Fortunately for

scholars, Mashtots is known in the

historical record.

One of his

disciples, named Koriun, wrote a

biography of his mentor, which records

many details of his life as well as the

process by which he formulated his

alphabet. The biography tells us that

Mashtots came from an aristocratic

family, that he served in the royal

court, and that he was ordained a priest

and founded several monasteries. With

the support of King Vramshapuh, and with

the aid of a Greek scribe named Ruphanos,

he embarked on a project to develop an

Armenian writing system.

Mashtots

studied various scripts as models,

including Greek and Syriac. He might

also have given careful consideration to

a version of Aramaic script developed by

the Parthian prophet Mani, promulgator

of the gnostic doctrine of Manichaeism.

According to Koriun, Mashtots' synthesis

of all these elements came to him in a

dream, resulting in a 36-character

alphabet. Two more characters were added

during the Middle Ages, bringing the

number of letters in the present-day

Armenian alphabet to 38.

According to

Russell, this synthesis reflects a

deliberate effort on Mashtots' part to

borrow elements from Eastern scripts but

reorient them to give them a more

Western character. All known alphabets

are derived ultimately from the

letterforms of the Phoenicians, but

Eastern writing tends more toward the

horizontal while Western alphabets

emphasize the vertical. Mashtots'

preference for vertical elements

reflects his effort to reorient Armenia

toward the Christian West.

More

information about Mashtots' alphabet has

been gleaned through careful study of

manuscripts. In recent years, computer

analysis has helped scholars to focus

with greater precision on the formation

and evolution of letter shapes. One of

the pioneers in this field, Michael

Stone, professor of Armenian at Hebrew

University in Jerusalem, was the keynote

speaker at the conference. Stone is the

chief author of the recently published

"Album of Armenian Paleography," which

uses computer techniques to analyze the

development of letters over time and is

a great help in accurately dating

manuscripts.

Besides

studying the letter shapes, scholars

have also tried to understand Mashtots'

reasons for ordering the letters as he

did.

Russell, who

has studied this problem and delivered a

paper on the subject, believes that the

order of the letters reflects his

familiarity with number symbolism of the

sort found in a Hebrew text called the "Sepher

Yetsira," or "Book of Creation," thought

to be an early work in the kabbalistic

tradition.

One measure of

the alphabet's success is the fact that

there have been few changes in the

letters or in the spelling of words

since Mashtots created it in the fifth

century.

"This is a very

striking circumstance," Russell said,

"especially when you compare it with

English where spelling has changed a

great deal in just the last 500 years.

It shows that the Armenian alphabet was

already so perfect that there was little

reason for it to change."

Perhaps an even

more convincing argument for the

importance of Mashtots' achievement is

the survival of the Armenian people

through a long and often trying history.

"Mashtots' real

achievement was to create a culture that

became a repository for both Eastern and

Western traditions, that was

cosmopolitan, but had a strong anchor of

its own. He made Armenia a culture of

the book, a 'bibliocracy,' and that has

been their key to survival, because you

can carry a book into exile, but you

can't carry mountains and trees."

James Russell

organized a conference to discuss the

fifth century Armenian alphabet invented

by St. Mesrops Mashtots. Russell said, 'Mashtots'

principal purpose in inventing the

alphabet was to change Armenia's

cultural orientation from the Iranian

East to the Mediterranean West.'

Mesrop Mashtots

Saint Mesrop Mashtots (Armenian: "Մեսրոպ

Մաշտոց", W. Armenian pronounced

Mesrob Mashdots) (360 - February 17,

440) was an Armenian monk,

theologian and linguist. He was born

in Hassik, Taron, Persian Empire

(today's Armenia).

Saint Mesrob is best known for

having invented the Armenian

Alphabet, which was a fundamental

step in strengthening the Armenian

Church, the government of the

Armenian Kingdom, and ultimately the

bond between Armenians in the

Armenian Kingdom, the Byzantine

Empire, and the Persian Empire. He

is also traditionally believed to

have invented the Georgian alphabet

but this belief does not stand up to

scientific scrutiny. In Georgia the

credit is usually given to King

Farnavaz. According to the

Matenadaran, a

monument and museum in Yerevan

dedicated to Mesrob Mashdots, he

also invented the Caucasian Albanian

alphabet and even the Ethiopian one

as well.

He is buried in Oshakan Church, a

village of the same name 8 km

southwest from Astarak_Town.

Oshakan Church

TOP

1875

AD -

Aragatsotn Marz

Oshakan Church - where

Mesrop Mashdots is

buried

Mesrop Mashtots statue

in Oshakan Village

Language and Literature

Armenian

literature began to develop with the

creation of the Armenian alphabet in

405-406 A.D. and the subsequent

translation of the Bible into Armenian.

Amongst the first texts to be translated

and studied were those of the great

Greek philosophers, politicians and

theologians. The study of these ancient

thinkers allowed for the

deprovincialization of the Armenian

culture. It also helps to explain why

the first texts written by Armenians are

neither naive nor primitive. One such

early piece was the epic poem "David

of Sasun," celebrating the efforts

of the Armenian bravemen who fought

against Arab domination and for the

freedom of the Armenian people.

The

oldest form of poetry, the hymn of

religious inspiration, has played a

major role in Armenian literature for

centuries. This lyrical poetry, a

combination of poetry and chant designed

for use in religious services, has been

written by the Armenians since the 5th

century.

Religious

lyricism reached its pinnacle in the

10th century with the works of Grigor

of Narek. His masterpiece, the

Narek, is one of the most widely

read works in Armenia.

The

12th century witnessed the rise of yet

another summit of medieval lyricism in

the person of Nerses Shnorhali

(the Gracious). This Catholicos left his

Lamentations on the Fall of Edessa and

many sharakans, or hymns,

used in the Armenian mass. Grigor and

Nerses lived and worked during the

"Golden Age" of Armenian literature as

the art of writing was flourishing. It

was toward the end of this period

(1095-1344) that poetry, including poems

on love and other secular themes, began

to appear and grow as an important force

in Armenian literature.

In the 13th and

14th centuries, Constantine of Erznka

began to write poetry of spring, love,

light and beauty, images which he

allegorically exalts the great mysteries

of Christianity. In Constantine one can

see a broadening of the poetry, a

movement away from more rigid

ecclesiastical terminology and toward a

freer, more open use of language.

In the 15th and

16th centuries, love poetry came to

exist in Armenia. Basically common to

all Eastern literatures, love poetry and

its forms were recreated in Armenia, a

country that had no such tradition

behind it. Nahapet K'utchak

embodied this new movement in poetry.

This new

poetic form continued to the time of

Sayat Nova. This greatest of writers

composed in Armenian, Azeri and

Georgian, singing of courtly love and

the unattainable beauty of the beloved.

The

death of Sayat Nova, in 1795, came on

the brink of the modern era. At this

time in history, the world was becoming

increasingly integrated. Armenian

children were being educated in the

universities of Europe. A new spirit

emerged, a lay spirit. Works once

thought to be vulgar, written in the

laic tongue of the commoner, finally

attained the dignity of literature. New

genres such as the novel, the ballad and

the short story were born as Armenians

were affected by the currents of

rationalism, symbolism and decadence

encompassing Europe; but, the themes of

these works remained traditionally

Armenian. Authors wrote of the land and

its peasant customs, the coveted

fatherland, and the yearning for

freedom.

The

nineteenth century beheld a great

literary movement that was to give rise

to modern Armenian literature. The

veritable creator of modern Armenian

literature was Khatchatour Abovian

(1804-1848). Abovian was the first

author to abandon the classical Armenian

and adopt the modern for his works, thus

ensuring their diffusion. Abovian's most

famed work, The Wounds of Armenia,

returns to the theme of the Armenian

people's suffering under foreign

domination. Khatchatour Abovian

dedicated his life to writing and

educating others on the subject of

Armenia and her people.

The

Armenian national movement was given

impulse by yet another great writer.

Raffi (Hakop Melik-Hakopian) was the

grand romanticist of Armenian

literature. In his works, Raffi revived

the grandeur of Armenia's historic past.

In the story "Gaizer," the heroes fight

for the liberation of their people. This

theme of oppression under foreign rule

is also evident in the works "Djelaledin"

and "Khente."

The literary

tradition of Khatchatour Abovian and

Raffi was continued even as Armenia came

under Communist rule. This revival of

tradition was carried out by such

writers and poets as Hovhaness

Toumanian, Yeghisheh Charentz and

the like. This revival took place under

the Communist system, much restricting

the freedom of expression of the

writers.

In the late

1960's, under Brezhnev, a new generation

of Armenian writers emerged. As Armenian

history of the 1920's and of the

Genocide came to be more openly

discussed, writers like Paruir Sevak,

Gevork Emin and Hovhanness Shiraz

began a new era of literature.

Today

literature thrives in the Republic of

Armenia as well as in the Diaspora.

Writers use one of two standardized

vernacular dialects, Westerns

Armenian and Eastern Armenian,

whose names reflect their geographic

origins.

Throughout centuries of foreign

domination the retention of the Armenian

language seems to have been one of the

people's greatest defenses against

assimilation. It is difficult to express

the deep feeling Armenians have for

their language, which many regard as the

lifeblood of their culture.

TOP

Back to

Matenadaran ‘‘manuscript

store’’

Copyright © 1996-2005 Atlas of

Conflicts, Andrew Andersen. All rights

reserved. |