|

Armenia

|

|

|

Armenia (Akkadian Uraštu;

Old Persian Armina):

ancient kingdom, situated along the river Araxes (modern Aras), the

Upper

Tigris

and the Upper

Euphrates.

For the early history of Armenia, see

Urartu.

Achaemenid Armenia

From the mid-sixth century onward, Armenia was a

satrapy

of the

Achaemenid

empire; how it had become part of the kingdom of the

Persians, is unclear. One possibility is that the earlier

kingdom called Urartu had been subjected to

the

Median

empire, and this may have happened as early as 605, after

attacks by nomads who lived north of the

Caucasus (known to the Greeks as 'Scythians',

Sakesinai or

Cimmerians).

The Medians were overthrown by the Persian king

Cyrus

the Great in 550, and Urartu was annexed by the Persians at

the same time. Alternatively, Urartu retained its independence and was

conquered in

547,

after a direct Persian intervention.

|

|

An Armenian on the

East

Stairs of the

Apadana

of

Persepolis. |

However this may be, the country rebelled against its Persian overlords

after

the coup d'état

of the

Magian

usurper

Gaumāta

(or

Smerdis)

had been suppressed by the counter-coup of Darius

I the Great. The new king sent two armies against an unknown

Armenian

leader, commanded by the Persian

Vaumisa

and the Armenian

Dādarši.

Vaumisa managed to secure the road to Armenia on 31 December 522 in a

battle

near Izalā and continued to Autiyāra,

where he won his

second victory on 11 June 521. Both towns are situated on the banks of

the

Greater Zab river. Meanwhile, Dādarši defeated

the Armenians on 20 May 521 near Zuzza, on 30 May at Tigra and on 20

June

at Uyamā. The second name suggests that this second army

moved along

the Upper

Tigris.

These five battles, which are all mentioned in the

Behistun

inscription, meant the end of the uprising. From now on,

Armenia was a

stable

possession of the Achaemenid empire. |

|

Armenian coin, showing a colt

|

According to the Greek researcher

Herodotus

of Halicarnassus

(ca.480-ca.425), the tribes in the country belonged to the eighteenth

and nineteenth tax districts. Every year, they had to pay five hundred

silver talents. The geographer

Strabo

of Amasia mentions another tax: 20,000 colts.

Under Persian rule, the Urartian language -related to

Hurrian-

was replaced

by Armenian, which was the tongue of the common people. Probably, this

was not caused by ethnic, but by political changes: when the Persians

had conquered the country, they favored the latter

language,

which is related to Greek and -at a distance- Persian.

|

|

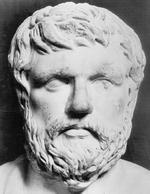

Xenophon |

Although the Armenians seem to have called themselves Haikh,

Herodotus makes in his Histories a distinction

between the Armenians

and Alarodians (a rendering of "Urartians"). He also mentions the

Chaldaioi,

Kolchoi, Makrones, Mares, Moschoi, Mossynoikoi, Saspeires, Tibarenoi (Tabali

in Persian), tribes that lived in Armenia (or in its neighborhood).

Armenia was a tribal society, which means that

the social and political units are

loosely

organized; old tribes disappear as new ones come into being, depending

on the situation. The Athenian author

Xenophon

(ca.430-ca.355) informs us about it in book four of his Anabasis.

He describes at great length how in 401/400 BCE an army of Greek

mercenaries,

which had supported the Persian pretender

Cyrus

the Younger, had to fight its way back from

Babylonia

to the Black Sea

through Armenia.

From the tribes mentioned by Herodotus, Xenophon also

mentions

the

Chaldaioi, Kolchoi, Makrones, Mossynoikoi and Tibarenoi, but

introduces

the Chalybes, Drilai, Kardouchoi and Taochoi.

|

|

A fertile mountain plain between Savsat and Ardahan. |

Herodotus

already knew that Armenia was rich in cattle (Histories,

5.49). Most tribesmen were poor cattle breeders who roamed with their

herds

-sheep, cows, horses- between the summer's and winter's pasture.

Xenophon

mentions no cities, but gives fine description of village live.

[A group of our

soldiers] surprised the

villagers with their

headman, and seventeen colts which were being reared as a tribute for

the

[Persian] king, and, last of all, the headman's daughter, a young bride

only eight days wed. Her husband had gone off to chase hares, and so he

escaped being taken with the other villagers. The houses were

underground

structures with an aperture like the mouth of a well by which to enter,

but they were broad and spacious below. The entrance for the beasts of

burden was dug out, but the human occupants descended by a ladder. In

these

dwellings were to be found goats and sheep and cattle, and cocks and

hens,

with their various progeny. The flocks and herds were all reared under

cover upon green food. There were stores within of wheat and barley and

vegetables, and wine made from barley [i.e., beer]

in great big

bowls; the grains of barley malt lay floating in the beverage up to the

lip of the vessel, and reeds lay in them, some longer, some shorter,

without

joints; when you were thirsty you must take one of these into your

mouth,

and suck. The beverage without admixture of water was very strong, and

of a delicious flavor to certain palates, but the taste must be

acquired.

[Anabasis

4.24-26]

|

|

|

In short, Xenophon's Armenians were a primitive nation, and it comes

as no surprise that Xenophon mentions that their warriors fought with

simple

weapons, such as slings and arrows.

The Persian garrisons, on the other hand, were oases of

luxury. For

example,

somewhere near the

Tigris Xenophon

visited a palace that could be used by the satrap; he saw houses with

storage

towers, which were probably used by the officers (4.4.2). Xenophon

mentions

an artificial road leading toward this settlement (4.3.5). In the

neighborhood

of a second Persian village, Xenophon's men found great supplies of

beef

(a delicatessen), barley, wine, raisins and pods (4.4.9). This is

confirmed

by the archaeological evidence: e.g., wall paintings were discovered at

Arin-Berd.

Independent kingdom

One of the last Persian satraps of Armenia was

Artašata, who became

king of Persia under the name

Darius

III Codomannus (336-330). During his reign, the

Macedonian

king

Alexander

the Great conquered the Achaemenid empire (between 334 and

330), and

Armenia regained its autonomy. (We learn of a new tribe, the Albanoi.)

Several kings are known from this period:

|

|

|

| Orontes II |

c.330

|

| Orontes III |

c.320 - c.280

|

| Samus |

c.260

|

| Arsames |

c.260 - c.230

|

| Xerxes |

c.220 - 212

|

| Orontes |

212 - c.200

|

|

|

Coin of Tigranes II the Great of Armenia, British Museum. |

After

200, parts of Armenia became incorporated in the

Seleucid

empire under king

Antiochus

III the Great. Soon, the country regained its

independence in the form

of two small kingdoms, west and east of the Euphrates. The western

kingdom

was known as Lesser Armenia and ruled by king Zariadris; the other

state

was called Greater Armenia and ruled by Zariadris' son Artaxias

(189-164). The latter rebuilt -following an advice of his

Carthaginian

friend

Hannibal-

Yerevan in 188, called it Artaxata, and made it his capital.

The younger capital Tigranocerta was built by a

descendant of Artaxias,

Tigranes

II the Great (ruled c.95-c.55), who had been able to reunite

Armenia and briefly ruled over the entire East,

but was defeated by the Roman generals Lucullus in 69 and Pompey in 66

BCE.

|

|

"Armenia Capta": Roman coin, commemorating Trajan's temporary conquest. |

Armenia between Rome and

Parthia

From now on, Armenia was one of the

battlegrounds between the Romans and the Parthians,

who had replaced the Seleucids in what is now Iraq. Several Roman

commanders, like Crassus (53 BCE) and Marc Antony (36) attempted to add

Armenia to the Mediterranean Empire in order to have a bulwark against

the Parthians. The latter came close to success: king Artavasdes II

submitted to Rome and Armenians fought for Marc Antony at

Actium.

As is well-known, Marc Antony and his wife

Cleopatra VII Philopator

met their end in 30 BCE, and their son Alexander Helius, who was

supposed to be king of Armenia, never ascended to the throne. Instead, a

son of Artavasdes II, Artaxes, became king, only to be replaced by

Tigranes III by order of

Augustus' general

Tiberius

in 20.

|

|

| |

Dynastic quarrels forced Rome to intervene several

times. At the

beginning of our era, it was Augustus' grandson

Gaius

Caesar who invaded Armenia. The situation remained

chaotic, because both Rome and Parthia

tried to gain control of this fertile country. But slowly, an agreement

was growing that the Euphrates was to be the frontier between the

mutual zones of influence. Lesser Armania, west of the

Euphrates, was included

in the

province

of

Cappadocia,

but Greater Armenia remained independent.

According to a treaty that had been concluded by

Augustus

and his Parthian colleague Phraates IV, the Romans had the right to

appoint

the Armenian kings. However, in 54 CE the Parthian king

Vologases

I, using an internal crisis in Armenia and a change of government in

Rome, installed his brother Tiridates as king of Armenia.

This deliberate provocation led to war, and to the sack of Artaxata in

58 by the Roman commander

Corbulo.

Tiridates was forced to go to Rome to be crowned by the young emperor

Nero.

Slowly, Rome was increasing its influence, and when

Vespasian

had added Commagene to the empire, a legionary base was created in

Satala,

controlling access to Armenia. As a rule, the Romans were permitted to

select a king from a member of

the royal family, which, through Tiridates, was originally Parthian.

However,

the country was briefly occupied by the Roman emperor

Trajan

between 114 and 117 CE. His successor

Hadrian

gave up the conquests.

Generally speaking, the second century was quiet,

although in 161-165, the Parthians and Romans went to war again. The

Parthians were defeated by

Lucius

Verus,

and Rome's power increased even more, but Armenia retained its

independence, although from now on, it was Rome's loyal ally against

Parthia. For instance, when

Septimius

Severus attacked the Parthian capital

Ctesiphon,

Armenian soldiers were in his army. They had little alternative,

because Severus had added

Mesopotamia

to the empire, which meant that all roads between Armenia and the south

were now controlled by Rome.

| Artaxias |

c.189 - c.164

|

| Tigranes I |

c.164 - ?

|

| Artavasdes I |

? - c.95

|

|

Tigranes

II the Great |

c.95 - c.55

|

| Artavasdes II |

55 - 34

|

| Artaxes |

34 - 20

|

| Tigranes III |

20 - c.8

|

| Tigranes IV |

c.8 - 1 CE

|

| Artavasdes II |

[pretender]

|

| Ariobarzanes |

c.2 - c.4

|

| Artavasdes III |

c.4 - c.6

|

| Tigranes V and Erato |

c.6 - ?

|

| Interregnum |

|

| Artaxias |

18 - c.34

|

| Vonones |

[pro-Roman, Parthian pretender]

|

| Arsaces of Parthia |

c.34 - 36

|

| Mithridates of Iberia |

36 - 51

|

| Radamistus |

[pretender]

|

| Tiridates |

51 - 59

|

| Tigranes VI 'the Cappadocian' |

59 - 62

|

| Tiridates (restored) |

63 - 75

|

| Axidares |

c.110

|

| Parthamasiris |

113 - 114

|

| Sanatruces |

c.115

|

| Roman province |

114 - 117

|

| Vologases |

117 - c.140

|

| Unknown |

|

| Pacorus |

161 - 163

|

| Sohaemus |

164 - c.175

|

| Unknown |

|

| Tiridates II |

c.215

|

| Unknown |

|

| Tiridates III |

c.287 - 330

|

|

|

|

Armenia between Rome and Persia

In the second quarter of the third century, the Parthian Empire was

replaced by the Persian Empire of the

Sasanian

dynasty, a more aggressive power than its predecessor. Several times,

the Sasanians attempted to add Armenia to their possessions, but they

were

repulsed by Armenian kings and Roman generals, although

often with great difficulty. The situation was restored to Rome's

advantage again by the emperor

Carus.

Meanwhile, a religious shift was taking place: Christianity was

spreading throughout the East. Although the Armenian Church has claimed

that it was founded by the apostles Thaddeus and

Bartholomew, the

first missionaries appear to have visited the country along the

Araxes much later. The breakthrough was in the year 303, when Gregory

the Illuminator (257-325) converted Tiridates III. For the first time

in history, an entire state became Christian. (The

Roman emperors Diocletian

and

Galerius,

who were persecuting the new

faith, will not have appreciated this.) The Armenian Church has

remained independent and does not accept several decisions of the

Ecumenical

Councils.

In the second half of the fourth century, the Sasanian king Shapur II

was able push back Rome, and gained influence in Armenia, which was

recognized by the Roman emperor

Theodosius

in 384, when he signed a treaty with Shapur's son Shapur III. In 428,

the Romans and Persians divided the ancient kingdom. Its traditions

survived in the Armenian Church. |

|

| |

Note

The table of kings is based on E.J. Bickermann, Chronology of the Ancient World

(1980²).

|

© Jona Lendering for

Livius.Org,

1998

Revision: 21 October 2007 |

|